SOA SPECIAL EPISODE 4 – Interviews With Illaminian Wanderers

by Shanna

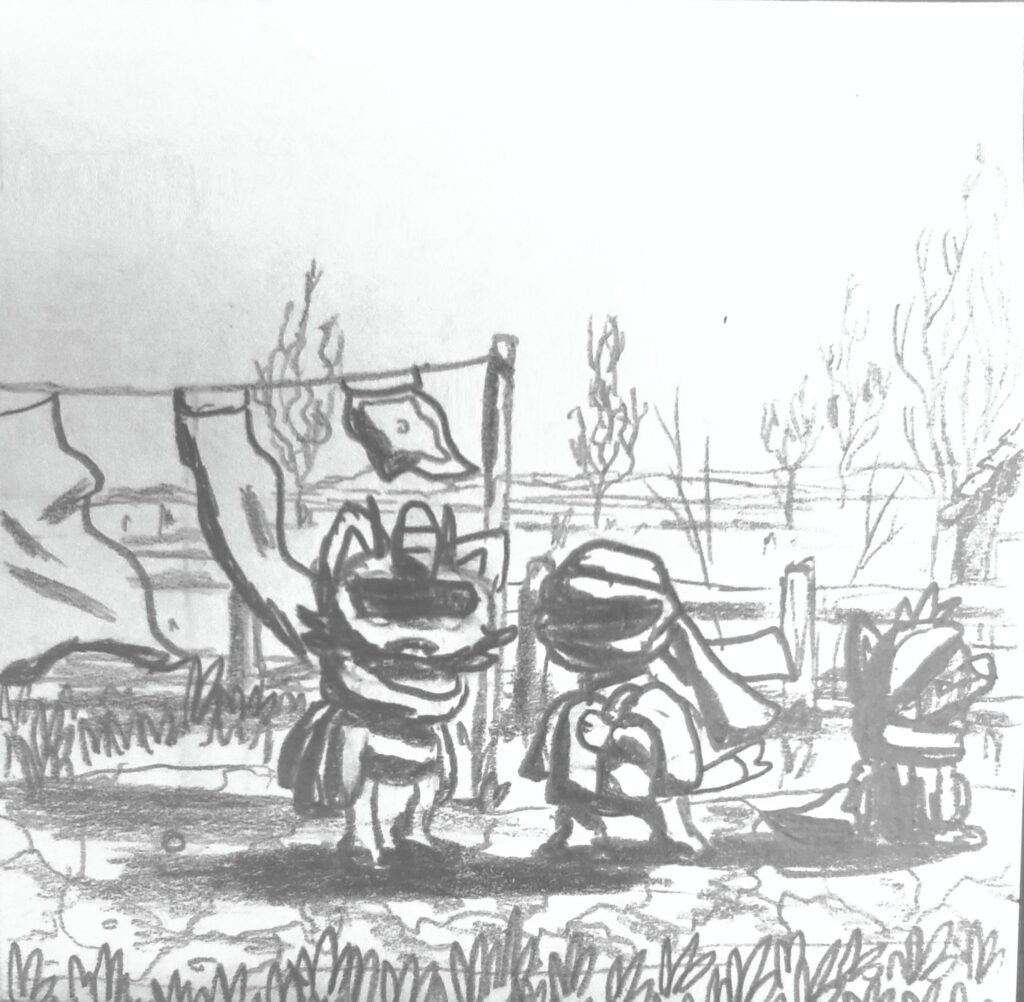

(“Photograph of Unknown Trio of Wanderers As They Loot Left-Behind Towels and Clothing from an Abandoned House in Order to Prepare for Winter” – Taken by Bareno Eavusi’Fimmonnehopi ~ 6T58, Often credited as the first look into Illaminian life during the droughts and the origin of the classical ‘Wanderer’ look including colorful scarves wrapped around the body and head.)

Interviews With Illaminian Wanderers

A story on my experience witnessing everyday life in ‘New Illamini’ during the droughts and governmental collapse. Written: 6th Turn 61 by Sulus of Yahneri

When I was a child, my grandfather would often tell me stories he’d heard from his father – my late great grandfather.

They were stories of our home country, a place that felt so exotic and far away, living on the Arcean east coast as we did.

My grandfather relayed second-hand tales of bright green fields stretching endlessly. They burst with a rainbow of swaying flowers, petals fluttering in cooled air. Mountains not of rock but of grass. Forests of enormous trees the likes of which no Pokemon in Arcea could fathom. Oceans of crystal-like water and metropolises that stretched as high as they were wide. Vast rivers with towns upon long-spanning bridges. And all of it was home to a vibrant, loving, community-focused culture.

This was the Illaminamo I was told about.

Often the misunderstood neighbor to Arcea, The United City-States of Illamini has, for over a century, become more and more reclusive. Slowly cutting itself off from outsider influence, the insular country has only grown isolated as the citizens and local governments focused more on themselves and their communities.

Of course, it wasn’t so long ago that Illaminamo was more open with its neighbors. A century and a half ago, Illaminamo and its exotic crops made it a major player in the world economy and its citizens often traveled abroad to live and financially grow. However, increasing tensions began to discourage travel and, in the wake of increasing hostility to their culture, many Illaminian nationals decided to return home, with only pockets of Illaminian-born citizens in Arcea remaining (as my family did in Yahneri Port).

For decades, this was the state of things – the mysterious country to the west once again became an isolated unknown that was little-understood by its neighbors. And for someone like me, a distant native by blood and even further by geography, it was an almost mythical place.

But, in recent years, everything has changed.

In the summer of 6th Turn 48, a bizarre weather phenomenon was observed in Illaminamo: a massive heat bubble seemed to form over the country, starting in the central Dsitdove region and expanding west to the coast and east to the Rocky Hills, even expanding south to the Quayoffi border. The bubble of dry heat has prevented any and all clouds from entering the sky over the country.

As it was the middle of harvest season when it began the phenomenon was not met with any concern. Although the country’s primary economy and food supply was in self-sustained farming of exotic crops there were a few measures in place to curtail a brief drought. Recent changes such as relaxing protections for bad harvests and canals being built to sustain large foreign farms made things a bit tougher but there was little cause for concern.

It was assumed, at the time, that the bubble would soon dissipate and rainfall would continue shortly.

The year is now 6th Turn 61.

Harsh droughts, famine and high temperatures have continued destroy once-beautiful Illaminamo.

Fields that were at one time green and teeming life have yellowed. The flowers no longer grow and a scent of hay permeates the air.

The dry grass has given way to wildfires which have become a national concern, causing even more widespread destruction to homes, villages and what farms are left. This has left travel within Illaminamo difficult as many paths are often engulfed in flames with too few fire brigades available to clear the fires.

The Central Illaminian government, for years cowardly and corrupt, has abandoned their country – vanishing into Quayoff with all their resources in tow and thousands more in capital embezzled and stolen from the ailing country.

Food stores have slowly been emptied out and ground water supply is depleting rapidly. The area surrounding Dsitdove has become an arid wasteland where the ground has become nothing but cracked mud and dirt where no life grows.

The army, left without taxpayer money to satisfy their wages, have either been inducted into Ushuhmou’s provisional national army or else have taken to highway robbery in order to feed themselves and their families.

Meanwhile the cities and villages, left to fend for themselves, have fallen back on ancient city-state governance laws that haven’t been used in over 600 years, before the time of Jyniarno’s unification of the country.

This is the state I found Illaminamo in when I visited for my investigation into the situation in the western country.

My name is Sulus of Yahneri. I stood on the soil of my ancestors to write about my findings – to write of the culture and the Pokemon left in the wake of this now 13 year crisis.

When first entering the country by the north Rocky Hills pass, I was met with resistance first by the Arcean army, then by the Ushuhmou provisional army after I had crossed the border. Immigration into Illaminamo is heavily discouraged, as it’s struggling with its resources as-is, even with a dwindling population.

While the Arcean army was merely discouraging verbally they quickly let me through after a go-ahead from their commander. The situation on the Illaminian side of the border, however, was much different.

Immediately after the hand-off I was taken by the Ushuhmou soldiers and brought into crumbling guard barracks. There was barely any furniture left – I could see discoloration in walls where decorative paintings and tapestries had been looted years ago.

The provisional soldiers seemed uncoordinated and operating without any oversight. They were simply given orders and left to self-govern at their post. They questioned me about my presence in the country extensively, held me until evening, before taking an ‘entry fee’ of 150 Arcean gold pieces which they split among themselves.

From there I was essentially thrown out of the fort and onto the main road with no further assistance. I had to locate my own means of transportation – I was lucky that an emigration cart from Dsitdove City arrived soon after. The confused driver agreed to take me to one of the few inns left in Jatvsoe City for the night.

What I saw along that carriage ride was exactly what you may expect: houses on the side of the road had been reduced to charred and blackened wood by the wildfires. Massive groups of families were flooding the road, walking in the opposite direction towards Arcea, with mothers clutching their babes and carts filled with whatever home amenities and supplies they could fit (As mid summer was the only time the north roads weren’t deathly cold). Smoke from a distant fire up north rolled thick over the darkening roadway. Everyone was coughing, myself included, mouths covered by wetted rags to block the miasma. My cart-puller hoped the fire was spreading up north – the Duphimevu region on the north coast still got the occasional rainfall so the fire would hopefully be snuffed out there.

As we moved into Jatvsoe City, my cart-puller told me to be careful around the soldiers here. The Ushuhmou provisional soldiers were on-edge due to political unrest around the country. There’d been tension and disagreement about who should control the new centralized government or indeed if there should be one at all.

The biggest contenders for power in Illaminamo currently are Ushuhmou City, Duphimevu City and Jatvsoe City. Meanwhile, Dsitdove City has strengthened its self-rule and independence, refusing to acknowledge any other central authority. Smaller villages have been quick to gain allegiance with larger cities they’re closest to – not out of loyalty but simply for the support in this harsh time. The Jatvsoe Prefecture government is some of the only officials from the old system that still remain, maintaining order and helping to direct citizens to safety. However, Ushuhmou City had been sending its considerable army to it and other cities to reestablish country-wide control.

My cart-driver suggested that I get out of Jatvsoe City as soon as morning came. Dsitdove City would be safer. This turned out to be a wise suggestion as anti-Ushuhmou riots broke out just as I was leaving at dawn. I only hope that cart-driver made it out safely…he had never even given me his name, only calling himself ‘A Homestaying Fool’. Ultimately, I had to slip out via another cart bound for Dsitdove City.

Reaching the Dsitdove region the next afternoon gave a full view of how dire the situation in Illaminamo had become. It was so dry that my lips cracked immediately. Dust storms plagued the road and the heat was intense – there was only just enough water to ration out to make it to the end of the journey. And in every direction there was nothing but miles and miles of cracked dirt. Nary a blade of grass, alive or dead, covered the landscape.

The situation wasn’t much better in the city – entire districts had been abandoned and have fallen into disrepair as looters tried to keep themselves and their family fed. Furniture and bricks were being sold on the black market to be exported to Arcea and Quayoff, or sometimes just to other Illaminians who needed them, all to eke out enough to eat. Passing these husks of buildings I could see hammocks and tents set up within, with swaths of squatters taking residence inside. Though Dsitdove City has an acting self-maintained protection army, they leave the squatters be, as there’s nowhere else to go.

The only viable districts to live in are three of the central ones. Here, the community has done its best to keep the area maintained and clean. The Illaminian tenants of taking care of one’s community shine brightest here, and despite the worsening conditions one can really feel a sense of camaraderie between family members and even complete strangers.

On my first day in the city I found the ration center where I could get my meals for the day – there was no process to verify my citizenship nor check if I was taking more than I should. A combination of the honor system and simply remembering faces was employed to surprising effect. One of the soldiers and ration center workers both recognized I was a new face on their block.

I explained I had come to report on the situation in Illaminamo. This caught their interest and I decided to ask them some questions about their experience here in the heart of the Old Country:

“Illamini is weak now, yet it’s stronger than ever, in some ways, I think.” One of the workers said to me. “When I was in school, before the droughts, you know…there was less friendliness. They were friendly but, you know…they would…they would always be clamoring for popularity. Who could be the most popular? The most well-liked. That’s all gone now, isn’t it? Nobody cares who is popular, they only care if you’re alive. So, I guess I would say, in a way, I suppose, that the droughts did some good.”

“It’s been awful.” Another worker at the ration center told me. “My friends have all gone to Arcea. My own family left me behind to run for Arcea. It’s been very lonely and that just makes everything harder to deal with. The sadness gets to you, at times. The hopelessness, it’s everywhere. People will come in telling me they buried another friend then cry when they see today’s ration is smaller than yesterday’s. I don’t know how much longer I can do this, but I can’t leave them. I can’t leave these Pokemon. I’m perhaps the only thing they’re happy to see all day. One of them called me an angel, simply for giving her a pack of crackers and some cheese. I don’t feel like an angel. I don’t feel like I’m helping people enough, if I’m honest. But there’s nothing else I can do.”

I remember my grandfather telling me once the Dsitdove region had the most resplendent farms in all of Tulaan. Now it’s all desert – the city is entirely unable to feed itself. Even the rations, which consisted of a pack of small biscuits with spreadable cheese, were a miracle to have.

Dsitdove City has been relying on imports of food and rations from Otumenipvu City. Otumenipvu is a city situated just west of the Rocky Hills and sits across the mountain range from the Arcean city of Souljraan – it’s been supplying Dsitdove City with food imported from Arcea.

I left the ration center and sat in an old café to eat. I’d been told that Chesto Cafes were, at one time, the pride of Illaminamo. It was a place to simply be around others, or to gather together. Poetry would be shared here. Art and music. Friends and strangers alike.

But this one was empty and quiet. The wood ceiling was missing a few planks and the Chesto was cold. I stared out the scuffed window, watching carts roll by. There was a large family in the cafe with me, two couples whose fathers were related by blood and their children plus grandparents. The family had been staying in one of the nearby inns to rest before making their way into Arcea. I was welcomed to sit with them and was joined by a family friend of theirs that was also visiting. I told them I came from Arcea and many of them ask me what it was like and if the rumors about unrest were true.

“See, we were actually given a cheap convoy to Dsitdove.” One of the parents said, explaining their experiences emigrating. “Dsitdove’s been very generous, giving cheap transport. We would never be able to afford getting ourselves all the way from Ushuhmou otherwise. The convoys can be tightly packed – I had to ride on top of the covered cart all the way from Ushuhmou and I thought I’d fall off!” He said with a laugh.

“I wish we did not have to go through Souljraan, did you hear?” Another parent said. “I hear of terrible things about Arceliaze. Terrible, terrible things. But it’s cheap to go there from Souljraan and the north path is too jammed up and becomes deathly cold really fast. What was it? Only warm enough to cross for two weeks?”

“Two and a half.” Her husband corrected.

“So we’d never make it before the winds came and killed us – going to Souljraan is just faster but I know they’re going to shove us in a cart to Arceliaze and that’ll be that. But, I guess, if dying due to unrest and such is a possibility in Arcea…then dying slowly due to starvation is a certainty in Illamini by now.”

I asked the family if they had any idea why Dsitdove was offering such cheap transport to Otumenipvu City.

“The ration I had here in Dsitdove City was the first full meal I’ve had in a month.” One of the grandparents told me. “The package was stamped with Otumenipvu Prefecture’s sigil. The pack had the words ‘Imported From Arcea’ printed on it. What’s that tell you, huh? Says to me we’re less refugees and more bargaining chip.”

I asked him why he’d think Arcea would want to trade refugees for food.

“I don’t know.” The grandparent told me. “But I always thought it suspicious how the Conduicy was openly interested in housing us in our time of need. Hah! When’s an Arcean ever cared a lick for an Illaminian?”

In the wake of these mass emigrations, whole villages and neighborhoods are left empty and abandoned. The family told me they’d passed farms of rotten fruit and vegetables, and buildings in disrepair.

During my second night at the inn I asked a few of the Dsitdove residents why it is they chose to stay. Some of them, naturally, cited economic reasons – it was hard to travel when you had little to begin with. Families with multiple incomes could manage fine but single Pokemon that had been unemployed were pretty much stuck. Others stayed because of family that were too old to move from Illaminamo, or other such reasons.

However, again and again there was another group that had a different answer: pride.

These were the group that called themselves ‘Sonepipvi funitvodu’, sometimes shortened to ‘Sone-Funi’, which in Illaminian means ‘Homestayers’.

That morning I met a man in Dsitdove – which in the interest of anonymity shall be referred to only as Solio – who was remaining in Illaminamo because his elderly mother was a proud Sone-Funi. My funds were quickly running low and Solio found my Illaminian acceptable enough that he could convince his mother to let me stay with them during my time in the country.

The family lived on the outskirts of Dsitdove, on a plot of land that, I’m told, was once a beautiful rolling paradise of orchards and farmland. What stands now is a desert of dirt, hay and dead trees, bleached by the sun. The horizon shimmered and hazed in the heat of the dry air, the sky a solid blue with not even a single cloud in the sky.

“Some children have only seen clouds in picture books.” Solio told me as we walked upon scorching, dusty gravel pathways. “The concept of clouds confuse some children. Rain may as well be a fairy tale. Imagine, a seven year old that will tell you ‘water that falls from the sky? I don’t believe in that kid’s stuff!’”

“Doesn’t Duphimevu City still get rain?” I asked.

“Perhaps, but many Pokemon die where they are born, especially in Illamini. And in Dsitdove, there hasn’t been a cloud in thirteen years.”

We came to Solio’s family estate. A rather impressive house stood, with that signature Illaminian light wood color with brightly painted colors and architecture sporting sheer spires and sharpened embellishments, as though it were the wings of a Zubat flaring before you. To an Illaminian, such an overwhelming visage brings comfort – to enter such a place is to know security with all inside.

The only other additions to the estate were a forgotten and overgrown shack and a family-run general store. It looked as though it got much more use back when there were visitors.

We met with the mother, a woman I’ll refer to as ‘Ms.Okae’, and she was actually pleased to hear I was visiting from Arcea.

“You are perhaps a few generations removed but you still have Illaminian blood in your veins. Any Arcean would consider that poison enough, I’m sure.” She said to me. “Old Illamini needs her people to come home, not abandon her in her time of need.”

She would continue to relay to me her position (rather unprompted).

“I can see everything from here. In times of strife, like the blight plague hundreds of years ago, all you ever hear is that Illaminians banded together to help one another. When Arcea invaded and stole our land, we banded together with Jyiniarno to take our land back and expel the invaders – to bring Illaminians home to their native land.

“Yet today, after a mere thirteen years of simple dryness, what happens? Cowards and traitors turn tail, saying they would rather be Quayoffi or, Golden One forbid, Arcean than weather a little hardship for the country and Pokemon that coddled them and fed them and called them family. This drought is a bump in the road – it is a minuscule problem compared to the hardship of our ancestors.

“This is all because of how much we mingled with Arceans back in 5th turn – we inherited too much of their selfishness and now it’s pushed out the Illamini sense of community. Now Illaminian Pokemon think only of themselves. If they’d all stayed the country would have been fine. And when the rain returns and all is well again I can promise: we will not welcome them back. They chose their home! And the true-blooded Illaminians chose Illamini!”

I asked Ms.Okae if she knew anyone who left personally.

“Former friends. My ex-sister and my ex-husband.” She said plainly, turning her nose up. “And my ex-daughter.”

Solio didn’t comment, simply leaving the room.

The next morning, I found the house empty with breakfast left on the table. Stepping outside, I found Ms.Okae and Solio helping one another set up the general store – a few customers had come by today, and they were from a group Ms.Okae had a deep appreciation for.

Among the Homestaying ‘Sone-Funi’ there is a particular subculture of cross-country survivalist. To these Pokemon, much like Ms.Okae, staying in Illaminamo is the highest honor and a moral imperative.

They loot abandoned homes by day and sleep under the stars by night, enjoying for themselves an unprecedented freedom that the civilized world a few years ago never afforded them.

They are simply called ‘Wanderers’.

These nomadic ‘Sone-Funi’ have taken to disconnecting themselves from their home societies, instead forming bonds with fellow travelers in smaller groups. They’re most easily recognizable by their multicolored headscarves made up of fabric taken from various sources – needed both for cold nights and harsh wind blowing dust and dried grass onto them. They make their living sourcing food wherever they can find it both in the wilderness and in abandoned homes. They oftentimes resell goods they’ve looted – things like silverware and plates and even furniture if they can fit it onto a cart. These stolen goods have been put into circulation among the remaining urban centers and often make excellent bargaining pieces for rations.

Indeed, the four Wanderers visiting Ms.Okae’s shop sported the same multicolored garments – one was a Diggersby, another a Quaxwell, and third a Shiftry, and a final one whose species was totally obscured to me under scarves and a loose-fitting full body cloak.

For a while I simply observed: Ms.Okae and Solio had been reducing how much they ate of their rations from Dsitdove City, giving themselves plenty of leftovers to sell. They also had an assortment of goods from their estate for sale, as well as other trinkets they’d managed to barter off other wanderers. For every ‘General Store’ in Old Illamini was now more akin to a bartering based pawn shop – Illaminian paper notes were only valuable for trading with Ushuhmou at this point. The most valuable prize was, of course, Roppi stones, which fetched a high price in Arcea and Quayoff – even a small Roppi stone could secure a family’s way out of the country.

Ms.Okae’s General Store happily traded for and with Roppi Stones – it is, in ways, the only viable currency in Illaminamo. But one way in which she differed from other stores is that she never took Arcean coins. “Toss away your dirt money,” she apparently would tell clients trying to use them. “Stones or Illamini paper only. Otherwise you must barter.”

I watched the Wanderers trade in some farming tools and disassembled parts of a carriage. One of them even handed over a dirt-covered child’s stuffed toy.

When I asked after the source of these objects, the Wanderers were rather forthcoming about the information (according to them I didn’t look like Wanderer material, thus I wouldn’t be competition):

“There’s a village a few miles out – the families living there recently pooled their money together to try and get some Roppi Stones from Ushuhmou so they could head for Arcea. Now the village is being picked clean by every nearby Wanderer.”

I asked if they would be heading back out that way.

“Yes. As soon as we finish here we will be returning to the village. We want to get as many Roppi stones as possible because that’s the easiest way to get things from families leaving the country. It seems that the more Roppi stones you have when you leave the better off you might be.”

I asked if they would be willing to let me tag along and help them carry things back to Ms.Okae. When questioned I explained I had come from Arcea to report on Illaminamo.

The atmosphere changed. Despite my fluent Illaminian, the fact I’d come from Arcea caused immediate friction – these Wanderers were proud Illaminian nationalists. One of them, the Diggersby, demanded to know what I’d been writing so far and wanted to read my notes to makes sure I wasn’t disparaging the country to a jeering Arcean audience.

“I know the Arceans are behind this drought. A thirteen year long drought doesn’t just happen.” The Diggersby told me – and I agreed to include it in my notes. “They’re probably working with Quayoff. Did you know there’s all kinds of dirty money in the cowardly Ushuhmou government? How do you think Qusv and Gisvomove leaders were able to get out so quickly? How do you think that, even after Illaminian currency became useless, so many government officials were able to get into Quayoff? They were paying their way out with Quayoff’s own money, which they took years ago in exchange for removing all the protections farmers used to have. Then they lied and said removing those protections was to save us money and economically enrich us. Look around and see our enrichment! They took that money so they would build canals for a bunch of remote farms owned by Quayoffi businesses. All those rivers dried quick when the droughts came.”

He conferred with his fellow Wanderers for a moment.

“Those Quayoffi-owned farms shut down and pulled out a year before the droughts. That’s proof enough!”

They continued their adamant assertions. With my promise to include their statements in my notes they reluctantly allowed me to tag along with them back to the unnamed village. So, I bid Solio and Ms.Okae farewell for the day and followed along with the Wanderers into the Dsitdove desert land.

We went off the path, taking a direct route – there was hardly any foliage to block our way and they had water to spare for a fourth traveler. Even still, I had to be sure to ration the water. The Wanderers joked often at my expense, telling me I was lucky it was only a short walk to the village.

Along the way, I did get to talk extensively with them. The fully-cloaked Wanderer didn’t talk much and I was told she was ‘the quiet and kindly sort’. Meanwhile, the Quaxwell was happy to give his background:

“I came from Gisvomove City, on the southern coast. It used to be a very fertile delta, but since we’re also by the ocean the lack of river water has caused sea water to creep up and completely destroy the water supply. The farms are unrecoverable, the place is more of an Ocean Swamp now. Most of my friends and family went to Quayoff almost immediately, as Gisvomove City is only a few miles from the Quayoffi border. But I had a friend that told me he was going to Duphimevu City to find work – it’d be a difficult journey going north, you see, because of the Dry Mountain that practically splits Illaminamo into north and south.

“But my friend, see, he figures he could spend all his money on a ferry ticket in the nearby Piccoe City and ride it all the way up the river to Jatvsoe City – then we’d only have to cross Waterfall Pass by foot and be on the north shore at Duphimevu City in no time. Well, it doesn’t quite work out that way. Because the river is packed with boats coming from the north to go into Quayoff – lots of rich Pokemon, right? Because it’s all rich Pokemon the tickets are impossibly expensive and we end up having to pool our money and sell off some of our stuff just to stow away on a return trip to Dsitdove City.

“This was, I think…6T53? About 5 years into the droughts, so Dsitdove City was a mess but it wasn’t the disaster it is right now. Really hot, too, I’d never felt so much dry heat in my life. So me and my friend are now trapped in the big city with no food, no money, nothing. The inns are crazy expensive because of everyone that’s flooding in from Ushuhmou City, which doesn’t even matter because they’re all fully booked. There’s more people in tents on the street than there are in any of the buildings, I mean the streets were packed. My friend and I have to sleep in an alleyway for the night.

“So my friend tells me he wants to try and make a run for Duphimevu City. Mind you, he’s telling me this while we’re both starving, thirsty, and standing in line for a pack of biscuits for the day. I tell him he wouldn’t make it halfway to Jatvsoe City and beg him to stay here but, oh no, he wouldn’t listen to me.”

The Quaxwell sighed and paused at this point, then added something he also wished for me to include in my notes:

“Vikino Eoavepvi’Ehsodumu – Jushio Aunu’Dji’Vsetqusve’Medrae i wowu i wihivu. Ti soitdo e mihhisi raitvu u e wifisi raitvu… Tqisu dji mu toevi epdji wuo. Noe nuhmoi i tepe i ou tupu tvevu ap Wehecupfu op raitvo amvono eppo. Tqisu fo sowifisvo qsitvu ti neo soatdosu ef essowesi e Duphimevini. Vo enu, enodu.”

“Vikino Eoavepvi’Ehsodumu – Jushio Aunu’Dji’Vsetqusve’Medrae is alive and well. If you can read this or see this at all…I hope you are, too. My wife is healthy and I’ve been a Wanderer these last few years. Hope to see you again soon if I ever manage to make it to Duphimevu, myself. Love you, man.”

The Quaxwell, Jushio, went on to tell me that’s essentially where the story ends:

“I managed to get a job as a grip for Rich families moving their things out of their manors onto carts bound for the ferry. After the work dried up a year later I just fell into Wanderer work with a group that rolled through town. It was a matter of just making money or, at least, getting stuff that’d get me food. We looked out for each other, but I did end up hopping groups until falling in with these other three.”

As he finished we reached our destination: the village (I never caught the name of it). I was feeling dead tired but, true to my word, I forced myself to pull my weight to help gather materials.

The village was nestled between two large hills, with a long bridge running across. A few trees with yellowed and browned leaves surrounded us in this small area, with a path leading deeper into the forest of dead trees. The ground was once again mostly dirt and gravel. A nearby wood fence looked recently repaired. Multiple log cabin houses dotted the surrounding area.

Despite it being an abandoned village, it was teeming with life. Other bands of Wanderers with colorful scarves walked between the wood log buildings and darkened stores. A large tent had been set up under the bridge, shielded from the hot sun, where a Wanderer group was selling Yaja and Totter, almost like a stand-up bar in the middle of a looting scene. In fact, for the ransacking of a village the atmosphere was rather relaxed and amicable. I was told there were occasional scuffles for resources, but every Wanderer group had at least one treasure trove village only they knew of, so there was little reason to fight over a spot everyone already knew. Not to mention, Illaminamo had no shortage of totally abandoned villages, and that number was only growing by the day.

My group started with a small house that sat next to what looked to be a once locally-owned rock shop – a cute novelty for anyone visiting, but now as empty as everything else. All the rocks were left behind, price tags and all – the owner certainly had no misunderstandings about their actual worth.

The Shiftry in our group slammed into the home’s front door, breaking it off one of its hinges. The whole structure shook and shuttered at the force and I could hear something clatter onto the floor inside.

As we stepped inside, I could see just how much was left behind. Chairs, side tables, rugs. The shelves had been cleared off save for a few trinkets. I could see outlines on the walls where paintings and photographs had been taken by the residents when they left. The food stores were left open and nearly empty, with only a few sacks of vegetables and rice left. Much to my companions’ delight there was some cheap Eksai left behind. Of course, they didn’t once consider drinking the Eksai, thinking only of the Roppi stones they could get for it. After all, drinking Eksai would only dehydrate them out in the Illaminian wilderness.

I didn’t see any children’s toys or a child-sized bed, only a single bedroom with a couple’s sized bed. Here, too, all the photos were taken but the rugs, sheets and all else were left behind.

The Shiftry told me this house reminded him of his grandmother’s home back in Qusv, when she was still alive. Hearing him say that, while at the same time he was rolling up a throw rug to sell back at Ms.Okae’s store, I couldn’t help but ask how he could find looting homes conscionable.

“Because I had my own home raided when I was only gone for a week on a food run. That was back in Qusv, where everyone was taking coastal ships to Quayoff. I was left with nothing, not even enough to escape to Arcea or Quayoff, myself. That’s a cross-country trip. So the Wanderer life chose me. I used to be furious and I’d wish I could find the ones that stole from me…but now I’m here, doing the same thing, and it made me realize how much I’d been hung up on my things.

“I was bitter and angry over someone taking my stuff so they could eat. Isn’t that weird? I wasn’t happy someone was now able to survive and eat – I was angry I now lacked objects. I used to get annoyed at old people that said young people like me were selfish…but isn’t it selfish for me to value my stuff over someone’s life? I didn’t realize how little I valued my community, the Pokemon that surround me. We don’t get a choice of when people do or don’t need help – part of being in a community means taking care of others even at our own expense.”

I asked if that makes it okay for him to steal someone else’s possessions.

“They left it behind because they don’t want it. It’ll now feed me – they’re taking care of me right now. I’ll sell it to Ms.Okae, and she’ll sell it to someone who needs and wants this rug. I’ll have Roppi stones, and I’ll give them to someone who needs to get to Arcea in exchange for food. Illamini takes care of me as I now take care of it.”

I asked if he would give the rug away for free – should a Pokemon only be allowed to have food if they have something to give in return?

“Survival requires we all pull our weight. It’s a pity but freeloaders always end up left behind…perhaps my Arcean mentality hasn’t left me completely!” He finished with a laugh.

Since we didn’t bring a cart it was up to us to determine what the most worthwhile things would be to carry back to Ms.Okae’s store. I was carrying a decorative gold statue and a sack of rice and grain. We took a moment to settle down under the village bridge by the Totter seller to relax before making the trek across the Duphimevu desert back to Solio and Ms.Okae. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to try any of this Wanderer Totter drink as we didn’t want to give away any of the loot.

The respite from the sun was welcome, and the surrounding hills created a tunnel of wind that rushed through the space under the bridge, cooling it off nicely. Many other teams were also resting. I heard some of them were here on their 10th or 11th run. On top of this, they all seemed to have their own different places to sell the things they took, from villages still occupied to out-of-the-way pawn brokers. There was even word that the ‘Old Illamini Market’ across the river was still alive and well, repurposed as a Wanderer trading hub now that all the companies and farmers were gone. Still others told us that they would go even further out, all the way to Ushuhmou, usually because they found some Illaminian paper money.

While we were relaxing, a cart emerged from the path coming out of the forest. Pulling it was a mother, whose family was in the cart she pulled, with their belongings in a second cart hitched to the back of the first. They came from Ushuhmou, but made a detour this way because the road to Jatvsoe was clogged up with refugees. Sitting with us under the bridge, they told me they were bound for Arcea (and in the face of some of my companions jeering they clarified they were some of the last on their block to do so. This did little to assuage the Wanderers’ ribbing).

To soothe them, the mother offered bags of fresh food for the Roppi Stones my companions were carrying. The father expressed worry about the trade, for food was surely to be scarce crossing the Dsitdove desert. The mother told him and me:

“We can ration. We will ration it out. I don’t want to end up in Arceliaze like Tumae did. You’ve heard the rumors, haven’t you? Horrible, horrible. No, I don’t want to stay in Arcea long. As soon as we reach Souljraan we get on the first cart bound for Quayoff and that’s that. Nobody wants to stay in Arcea but the price for a cart to Quayoff from Souljraan has increased, I’m told, yet it’s still cheaper than trying to ferry down by river, nevermind trying to get over the Dry Mountain. I’d rather cross a flat desert than go uphill on a desert mountain any day. Yes, yes, Quayoff is the way to go. And if any of you want to leave Illaminamo, save your Roppi stones and avoid going to or staying in Arcea at all costs.”

I asked her what she thought of those that did end up in Arcea.

“A pity. Such a pity. Arceans have never liked us and I’m not much fond of them, myself. Were it I could help I would but I have to secure my family first. It’s a shame not everyone can afford to go to Quayoff – Arcea is much cheaper for an Illaminian to run to. I hear they give free housing when you reach Arceliaze. A tempting trap, indeed, and many fall for it. I heard all the time in Ushuhmou Pokemon saying ‘well if I was just to do this then it wouldn’t be so bad’ or ‘I’m sure I can find a way to get around the bad parts – food, a job and a house is a better place to start than nothing at all.’ I wonder if they knew better all along and simply told themselves these things as they marched into Arceliaze, belly empty and with little other choice.”

I asked her if she was worried about her home being looted by Wanderers.

“I’ve seen the Wanderers plenty. My neighbor stepped out the door to go to Arcea and not five minutes later seven or six Wanderers stepped in the door to take whatever wasn’t nailed down. But they’re good Pokemon, good Pokemon. They sold me nice things for years. Food, too, and I never minded where it came from. The food would have rotted either way, wouldn’t it? They’re fine enough Pokemon, so I suppose they’ve already taken everything from my home. So there’s not much point worrying now – there’s nothing I can do about it. I have my family here and that will be all I need.”

I paused a moment. My companions had lost interest in the conversation, now happily snacking on the food, with one of them trading in an apple for a cup of Totter to drink. Amid the talking and laughter of the Wanderers, all of them surrounded by stolen goods in the skeleton of a village, I asked her a final question.

I asked if she would ever return to Illaminamo with her family.

“Even if this New Illamini recovers, the damage is done forever. There’s no going back. It will evolve and morph and transform into something I can’t recognize.” She said. “It’s a dead country. Dead. Dead. Dead…”

0 Comments